Many business leaders today recognize that customer-centric business strategies are a more sustainable approach to achieving a long-term competitive advantage than a focus on product innovation or operational excellence. Not surprisingly, enhancing customer relationships is a top priority for many companies today.

Central to this strategic positioning is the concept that customers are assets and—like any other corporate asset—can serve as an avenue to increased profitability if their value is properly measured, managed, and monetized. For example, understanding the value of individual customers allows a company to refine its acquisition tactics, thus securing new customers who are most likely to become highly profitable over time; to focus investments among existing customers, to realize their full growth potential; and to maximize the retention of its most valuable customers.

Despite widespread acknowledgment among academics and practitioners that a strategy built on customer value spurs business success, companies still struggle with the measurement, management, and monetization of customer value. To better understand the current state of companies’ successes and struggles with customer value, Peppers & Rogers Group conducted a research study to gain insight into such areas as understanding the use of customer value data within an organization, business performance and customer value, and the impact of customer value on marketing programs and marketing spend. Peppers & Rogers Group collected data from more than 230 business leaders from various industries and company sizes.

Understanding customer value

The term customer value is commonly used to denote lifetime value (the present value of all future profits generated by a customer). When further clarified by specifying the assumption that the company’s behavior toward the customer remains unchanged over time, lifetime value is known as actual value. Additionally, if the modification of a company’s own behavior toward the customer (based on insight into the customer’s needs) is taken into consideration, then the estimation of the customer’s future contributions is referred to as potential value—the value that the customer could represent.

About one fifth of the survey respondents report that customer value is primarily understood within their company as the sum of an individual customer’s revenue over a fixed period of time. Nearly half, however, understand customer value to mean lifetime value, while a third report that customer value is “a prediction of what an individual customer could be worth, if the customer’s future behavior changed in response to actions by the company.” Only 5 percent of respondents indicated that their company did not currently measure the value of individual customers.

What leading indicators do companies use to predict the value of individual customers? Among companies that understand customer value to be “lifetime value” or “potential value,” 32 percent use lifestyle changes, such as a change in employment, a new household address, or the birth of a child; 58 percent use lifetime value drivers, such as changes in the frequency of purchases or changes in the mix of products bought; 42 percent use behavioral cues, such as receiving a complaint or signing up for a newsletter; and 64 percent use attitudes, such as satisfaction or willingness to recommend the company. Few companies use all four categories of leading indicators: 43 percent of companies use one; 24 percent use two; 14 percent use three; and only 13 percent use all four. This presents an opportunity for many companies to improve the breadth of data they use to accurately predict customer value.

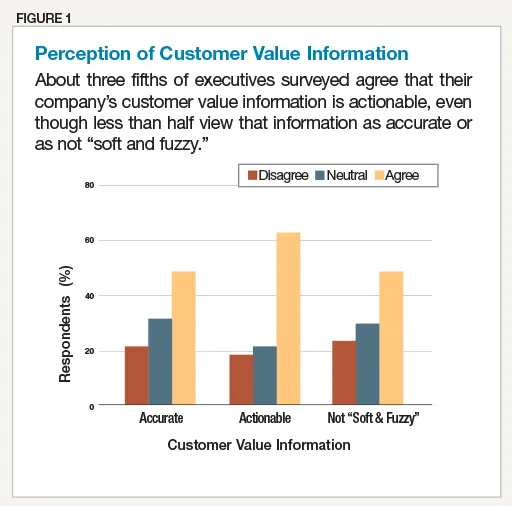

However a company computes customer value, not all respondents view that information as useful (see figure 1). While about two thirds somewhat agree or strongly agree that customer value information is actionable within their company, less than half view it as accurate or as not “soft and fuzzy,” suggesting that the quality of the customer value information has significant room for improvement in many companies.

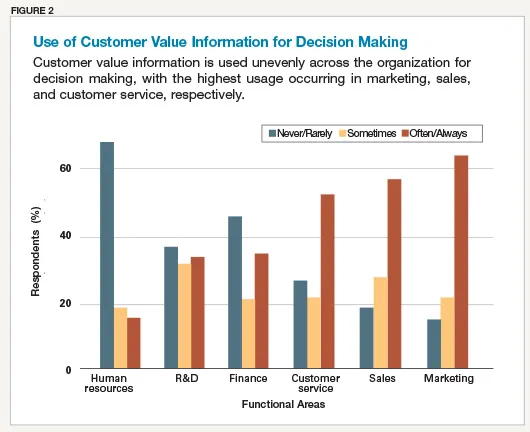

Using customer value information for strategic decision making varies by functional area within a company (see figure 2). About two thirds of respondents indicate that it is often or always used by marketing, followed closely by sales and customer service. Only about one third of companies report that finance uses customer value information often or always in making decisions, suggesting the need for a greater awareness of—and agreement with—the perspective that customers are assets.

Valuing individual customers

Performance. Only about one third of companies rate their current performance in measuring the value of individual customers as good or excellent, with more than double that number reporting poor or fair performance (see figure 3). Consequently, there is need for improvement for the majority of companies (92 percent), which fall short of excellence.

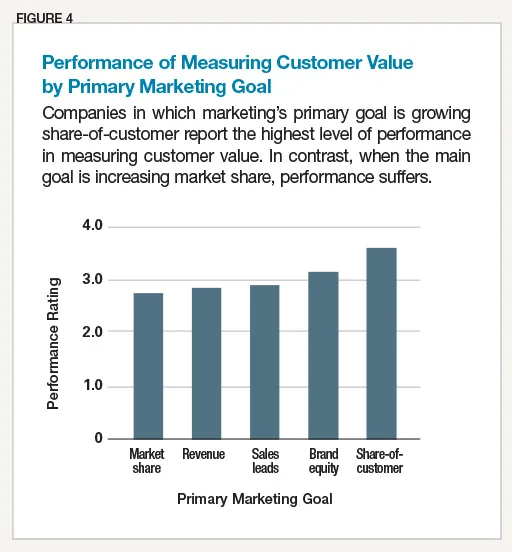

Interestingly, a company’s primary marketing goal impacts how adept the firm is at measuring the value of individual customers (see figure 4). When that marketing goal is increasing share-of-customer, performance is highest (mean of 3.6 on a rating scale where 5 = Excellent). In contrast, when the goal is increasing market share, the performance rating drops (2.8). For all marketing goals examined, however, the performance rating is less than “good” (4.0). For the goals of generating sales leads (2.9), increasing revenue (2.9), and increasing market share (2.8), the rating falls below “fair” (3.0).

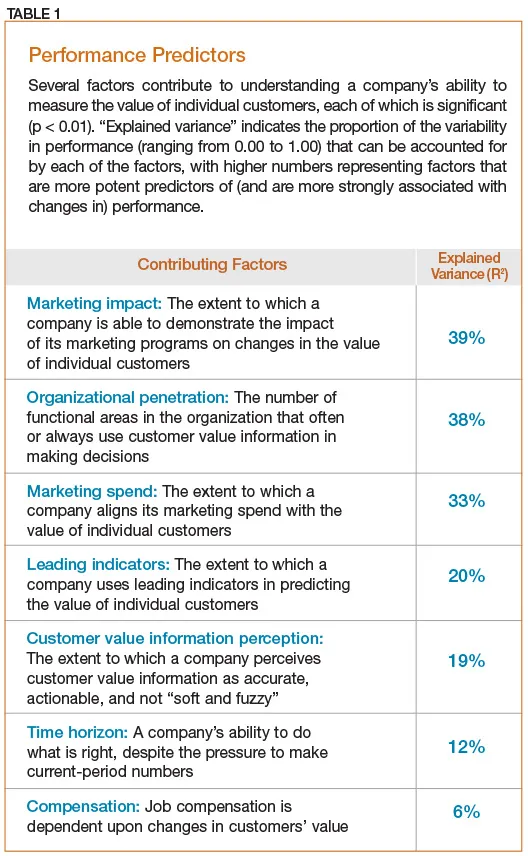

Several factors account for the variability in companies’ ability to measure the value of individual customers (see table 1). These include the extent to which a company uses customer value information in decision making; the use of leading indicators; and the perception of the quality of customer value information as accurate, actionable, and not “soft and fuzzy.” Additionally, whether a company focuses more on short- or long-term goals also influences performance. Taken together, these observations suggest that the strength of a company’s orientation toward customers is associated with higher levels of performance.

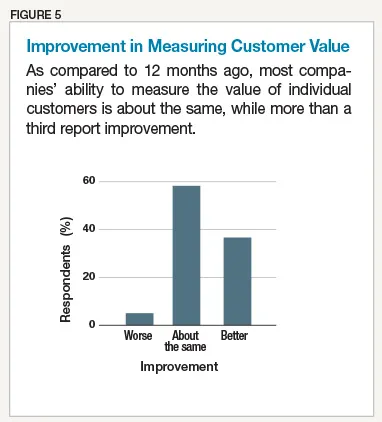

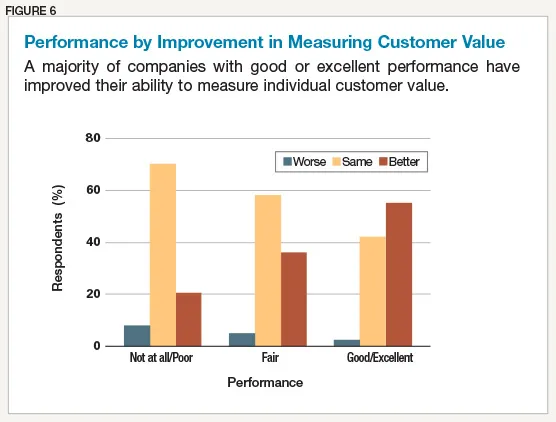

Improvement in Performance. As compared to 12 months ago, about one third of companies have improved their ability to measure the value of individual customers, while more than half have remained about the same. A small group (6 percent) reports deterioration in performance, however (see Figure 5). When improvement is examined in conjunction with performance (see Figure 6), a disturbing pattern emerges: Although a majority (54 percent) of good/excellent companies have improved their ability to measure customer value, comparatively few (21 percent) of the poor performers have exhibited improvement. As a consequence, the good have been getting better, but the challenges to advance remain more pronounced among the very companies that have the highest need to improve.

The primary factor explaining variability among companies’ improvements in measuring individual customer value is recognizing the criticality of customer trust. Companies (a) that believe customer trust is tied to the financial success of the business and (b) that consider how a proposed action may increase or decrease customer trust are most likely to exhibit improvement.

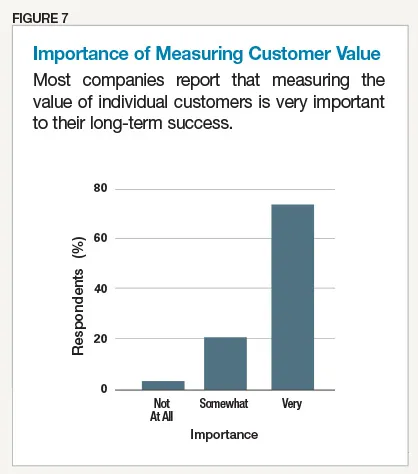

Importance. All but 3 percent of companies report that measuring the value of individual customers is somewhat or very important to their long-term success (see Figure 7).

As the importance of measuring individual customer value increases, so does the likelihood of its broad use across an organization for decision making. For the 22 percent of companies that considering using customer value in decision making to be somewhat important, the mean number of functional areas using that information is 1.9. In contrast, this number increases to 2.8 among the 75 percent of companies for which it is very important.

Importance also varies by a company’s primary marketing goal. For those companies seeking to increase share-of-customer, the mean importance rating (on a scale where 3 = Very) is 2.9, whereas for those focused on generating sales leads, the importance rating decreases to 2.6.

Performance x Importance. Several variables influence the performance of, and the importance placed on, measuring the value of individual customers. Most notably, these are: 1) whether job compensation is dependent on changes in customers’ value; 2) whether a company’s time horizon is short or long term; and 3) whether a company recognizes the criticality of customer trust.

1. Compensation. Respondents for whom job compensation is dependent on changes in customers’ value rate both the performance (3.4 on a scale where 5 = Excellent) and importance (2.9 on a scale where 3 = Very) of measuring the value of individual customers higher than those for whom there is no compensation dependency (2.8 and 2.6, respectively).

2. Time Horizon. Executives who somewhat or strongly agree with the statement “In my company, we can do what is right despite the pressure to make our current-period numbers” rate both the performance (3.3) and importance (2.8) of measuring individual customer value higher than those who strongly or somewhat disagree (2.6 and 2.6, respectively).

3. Trust. To measure trust, a composite of responses to the statements “My company believes that customer trust is tied to the financial success of the business” and “Whether a proposed action increases or decreases customer trust is used as a guideline in making decisions in my company” was formed. As trust increases from low to medium to high, both performance (2.3, 2.8, 3.3) and importance (2.4, 2.7, 2.8) of measuring individual customer value increase.

Both the performance of—and the importance placed on—measuring the value of individual customers, therefore, are mediated by aligning job compensation to changes in customers’ value, by the time horizon (short or long term) of a company, and by a company’s recognition of the criticality of customer trust.

Marketing impact and marketing spend

A company is able to monetize the measurement of customer value under two main circumstances: 1) when it is able to demonstrate the impact of its marketing programs on changes in customer value, thereby allowing the company to improve programs failing to meet expectations; and 2) when it is able to align its marketing spend with customer value, focusing resources on retaining the most valuable customers and developing customers with the greatest growth potential, for example.

Only 30 percent of companies are good or excellent at demonstrating the impact of their marketing programs on changes in the value of individual customers, with 60 percent rated as poor or fair, and 11 percent not at all able to document the linkage. Companies likewise struggle with aligning marketing spend to the value of individual customers, with only 16 percent reporting that it is done extensively or completely; 68 percent, somewhat or mostly; and 16 percent, not at all. Fourteen percent of companies are good/excellent at demonstrating the impact of their marketing programs on changes in the value of individual customers, and they are extensively/completely able to align marketing spend to the value of their individual customers.

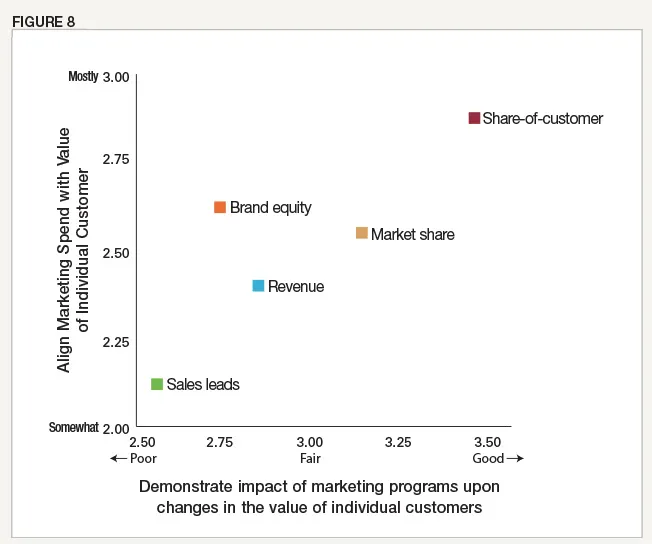

A company’s success in demonstrating the impact of marketing on customer value and aligning marketing resources based on customer value varies based on the primary of role of marketing (see figure 8). For companies in which marketing’s goal is increasing share-of-customer, both of these dimensions are rated highest. For companies in which marketing’s goal is generating sales leads, however, both dimensions are rated comparatively low. In all cases, however, the mean rating score for demonstrating the impact of marketing programs on changes in the value of individual customers is below “good” (on a scale where 5 = Excellent), and the mean rating score for aligning marketing resources based on customer value is below “fair” (5 =Completely), indicating that companies have room for advancement in both areas.

Conclusion

Despite broad agreement that measuring the value of individual customers is important to long-term success, companies of all sizes and types across industries still struggle to measure customer value and, for many, improvement remains elusive. Few companies use a broad mix of lifetime value drivers when estimating customer value, and less than half view the resulting information as accurate. As a consequence, the penetration of customer value information’s use across functional areas within the organization is limited, confined mostly to marketing, sales, and customer service.

Most companies are disadvantaged by their inability to monetize the measurement of individual customers’ value. They can neither demonstrate the impact of marketing programs on changes in customer value nor align marketing spend with the value of individual customers. Fortunately, there are opportunities to improve. These occur as a company’s time horizon shifts from short to long term, as the realization of the criticality of customer trust is heightened, as marketing’s primary goal evolves to a focus on increasing share-of-customer, and as job compensation is aligned with changes in customers’ value.