Customer centricity is essential to effective marketing. Astute marketers know this. When making marketing decisions, most marketers know they should recognize the importance of customers in achieving growth, should remember to balance the short- and long-term needs of the business, should seek to enhance trust with customers, and should measure changes in customer lifetime value. But how well are these principles actually practiced today? To find out, the Peppers and Rogers Group Institute for the Advancement of Customer Centricity conducted a basic research study1 among more than 200 professionals who know and follow the latest thinking in one-to-one marketing. Yet, even among this savvy audience, the directional results highlight the difficulty of applying customer-focused principles in today’s companies.

Growth

When asked to define the primary target for growth at their company, about two in five cited increases in the financial metrics of revenue or profit (see Figure 1 on page 46). Only about one in five measure growth through changes in share-of-customer or customer lifetime value, despite the fact that top-line revenue or bottom-line profit is known to be driven by effectively fulfilling an increasingly large proportion of customer needs, captured through increases in share-of-customer, or by improving customers’ experiences so as to enhance their future likelihood of purchasing and recommending the company, reflected in increases in their lifetime value. Organic growth recognizes the primacy of productive and authentic customer relationships, from which all other business benefits follow as a consequence.

Short Term and Long Term

Balancing the reality of the short term against the requirements for the long term continues to challenge many marketers. Slightly less than half of all respondents agree that their companies’ efforts to achieve short-term financial goals are not damaging the prospects for long-term success. Furthermore, there exists a willingness to reduce or delay investments in a variety of customer-focused areas in order to meet those short-term financial goals (see Figure 2), each of which may negatively impact a customer’s willingness to purchase from the company in the future. These include such activities as reducing or delaying investments in gathering and analyzing customer feedback and in improving customers’ experiences. On average, respondents identified 2.6 areas, with about three out of 10 naming four or more areas, the funding for which may suffer as a consequence of having to achieve short-term financial goals.

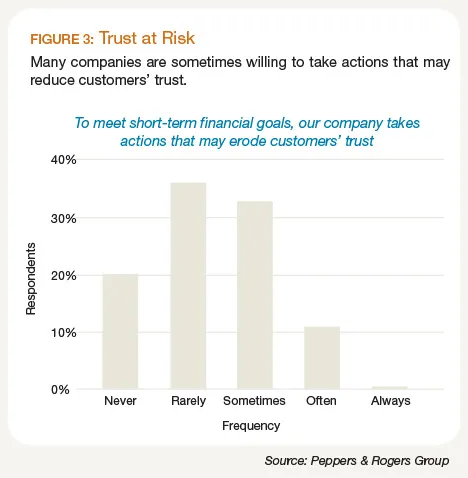

Trust

The pressure to meet short-term financial goals is sufficiently strong that four out of five companies report taking actions that may erode customers’ trust, with about two out of five stating that such actions occur sometimes, often, or always (see Figure 3). Public companies are nearly three times as likely as private companies to do so often or always, and, unfortunately, only one in five of all companies assert that it is never done at all. Since trust is the foundation for growing customer value over time, the willingness of some companies to occasionally make decisions that knowingly may erode that trust is particularly shortsighted.

Customer Lifetime Value

Consistent with the low percentage of companies monitoring growth through changes in customer lifetime value (CLV), only about two in five often or always calculate and include changes in CLV when reporting financial results. Three out of five companies do so rarely or never. In the absence of measuring CLV, a company cannot compute Return on Customer (ROC) and therefore cannot accurately assess the amount of value that is created per customer. “A firm relying on ROC will actually make different—and more managerially and financially beneficial—decisions than it would make by relying solely on ROI,” note Don Peppers and Martha Rogers, Ph.D.2

The reality of failing to quantitatively compute CLV is in stark contrast to the commonplace understanding that the quality of customers’ current experiences impacts their intention to spend more (or less) with the company in the future, and, as a result, the company gains (or loses) value at that instant. Nearly four out of five respondents agree or strongly agree with this perspective, with very few disagreeing or strongly disagreeing. Despite an intellectual understanding of the link between customers’ experiences and their lifetime value (and between CLV and company value), actually measuring and using customer lifetime value to make marketing decisions remains elusive.

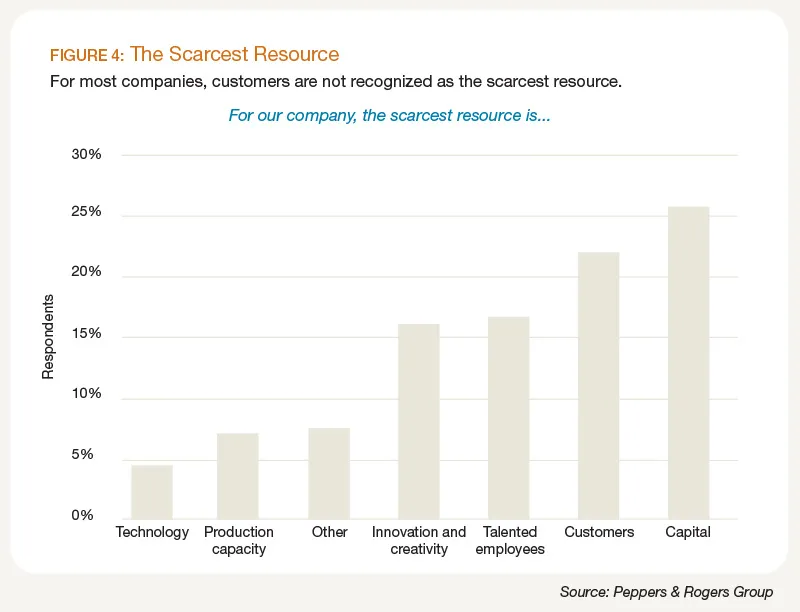

The disconnect may be due to companies not fully appreciating that customers are almost always the scarcest resource (see Figure 4 on page 48): In every market, their number is limited. Only about one in five state that the scarcest resource for their company is customers, with slightly more reporting that capital is the scarcest resource. Yet, “if you have a customer for your business, you can almost certainly get the capital you need to serve him,” Peppers and Rogers explain. “Because customers are your scarcest resource, every decision you make should be evaluated in terms of the return it generates on this resource. Your company should be making its decisions on the basis of Return on Customer.”3

Conclusion

Knowing the extent to which a marketing initiative creates (or destroys) value—i.e., augments (or depletes) a company’s reservoir of customer equity—is a prerequisite for making wise decisions that enhance the likelihood of a company’s long-term success. Return on Customer (ROC) is the metric that allows such assessments to be made. Fortunately, two thirds of respondents in this research state that their understanding of ROC is good, very good, or excellent. Yet, even among followers of one-to-one marketing, the practice of ROC appears to significantly lag the comprehension of the principles of ROC at this time. An emphasis on the short-term results—at the expense of the long term—is still too commonplace: reducing or delaying investments that strengthen customer relationships, sometimes taking actions that may erode customers’ trust, and rarely or never calculating and including changes in customer lifetime value when reporting financial results.

The problem of a disproportionate focus on the short term may arise from the failure of many companies to fully appreciate that customers are a scarce resource. The solution? Employ ROC as a metric to assist marketing professionals in balancing the reality of current-period cash against the requirement for growing customer lifetime value when making decisions. “If customers are your scarcest resource,” assert Peppers and Rogers, “then the more value you can create from each one, the more your business will be worth.”

Endnotes

1. Data were gathered from 223 subscribers and registered users to Peppers & Rogers Group’s 1to1 Media publications during the period of January 18 through February 4, 2010, the majority (87 percent) of whom hold positions at the manager, director, vice president, or president/C-level in either a publicly traded (27 percent) or privately held (73 percent) company.

2. Peppers, D. and Rogers, M. (2010) Return on Customer: A Core Metric of Value Creation. Customer Strategist, Volume 2, Issue 1, pp 30–39.

3. Peppers, D. and Rogers, M. (2005) Return on Customer: A Revolutionary Way to Measure and Strengthen Your Business. New York: Doubleday.