Customer strategy success stories have caught the attention of organizations in all industries, including the public sector. Companies like Apple and Amazon prove that customer focus benefits more than just consumers. The removal of friction from customer experiences also removes costs and inefficiencies from operations, and can improves a firm’s (or government’s) reputation. And that’s a narrative governments are interested in.

Take Saudi Arabia. Its economy, the largest in the Middle East region, has been growing at a considerable pace. Its leading position in the global oil market has propelled its national economic output to an average growth rate of 6 percent over the past three years. The Saudi labor market has grown along with it, and is a necessary part of the country’s continued expansion. It consists of a large number of foreign labor, both skilled and unskilled.

Neither Saudi Arabia’s reliance on oil nor its labor practices are sustainable over the long term. The Kingdom is looking to diversify its economy, decrease the national unemployment rate, and create a healthy and attractive labor market for both national and foreign workers.

In particular, the Ministry of Labor is taking transformative steps to change how labor disputes are handled. The Commission for the Settlement of Labor Disputes is responsible for resolving labor/employment-related disputes, and operates under the auspices of the Ministry of Labor. Employees who cannot settle disputes with their employer on their own go through this entity.

The Commission is comprised of three independent entities: the Reconciliation Office (RO), the Court of Instance (CI) and the Court of Appeal (CA)1 (see Figure 1).

Despite its supposed straightforward process, it has been widely reported that the life span of a case in the Commission could take months, and in some cases years, to get resolved. Often, the duration of the process is manipulated by one of the concerned parties to play in their favor at the expense of their opposition. And, there is no standardization when it comes to the number of sessions needed to move through the process, nor the amount of time in between each session.

The Ministry of Labor worked with Peppers & Rogers Group to identify and implement ways to improve the labor dispute process. As with other customer experience initiatives, the best way to transform was to assess the organization’s operations, processes, information, and technology, then recommend outside-in solutions that improve the external customer experience and internal structure.

We concluded that a number of factors had made the process inefficient and unproductive:

• Low attendance rate. By law, a ruling could not be issued if one of the litigants did not attend the scheduled session. Yet many plaintiffs work in remote locations and did not have a way to get to the scheduled session. Defendants often took advantage of this rule, leading to a higher number of sessions required to end a case.

• Misunderstanding of rights and responsibilities. The respective gaps between expected/actual services provided and expected/actual rights of employers and employees indirectly increased the number of sessions needed to end a case. This gap led to “clogging the system” by submitting and processing cases that are either outside the purview of the Commission or had no legal grounds.

• Inefficient case resolution. There were deficiencies in skills essential to resolve or close a case. This held especially true in the Reconciliation Office, where investigators did not undergo academic training aimed at equipping them with the necessary legal and interpersonal tools. The Commission did not require RO investigators to have a law or a Shari’a degree.

• Siloed entities. The RO, CI, and CA were three independent entities operating in silos with minimal communication processes. This led to misalignment of operational coordination and unnecessary bureaucracy. Moreover, the three entities servicing a particular city were in many cases geographically dispersed, obliging parties—usually unemployed migrant workers with limited resources—to travel long distances of more than 1,000 kilometers between an RO and its respective CI.

• Case handling capacity. Most of the Commission’s outlets were understaffed and short on investigators, judges, and especially administrative employees. This limited their ability to process new case applications and created bottlenecks.

• Organizational confusion. The absence of an organizational structure and clear job descriptions led to confusion and operational ambiguity. This directly impacted employee morale and productivity, which in turn eroded the service quality.

• Communication channels. There were no official communication channels to ensure delivery of hearing notifications, status updates, and information dissemination to concerned parties. With no proof of delivery there was opportunity for manipulation.

• Low automation. Automation was practically nonexistent within the Commission’s operations, causing many case files to be lost or misplaced. This led to an extraordinary amount of paperwork, bureaucracy, and outright wasteful processes.

These areas of opportunity—disparate systems, poor communications, organizational silos, inefficient processes—are common to many organizations in need of a major transformation around customers. They are often the result of a sole focus on internal operations, with little regard for the impact on customers or other external factors.

However, in this case, the state of the organization had human rights implications. At the forefront lies the individual migrant worker. Most vulnerable to abuse due to exploitative recruitment practices, language barriers, and limited monetary resources, the migrant plaintiff starts the litigation process at a severe disadvantage. The burden only gets heavier as the case span extends, leading many to simply give up and leave the country, or stay quiet in a risky or dangerous environment.

Additionally, the labor dispute system affects the Kingdom’s international reputation as a progressive country actively working toward enhancing the labor market and making it more attractive for both national and migrant workers. Businessweek cited Riyadh as the third worst city in the world to work in and qualified it as a “very high risk location.”2 And the Huffington Post placed the Kingdom in a category of working conditions second only to active conflict zones such as Somalia and Syria, where no legal protection exists.3 Clearly big change was needed.

Transformation touches all parts of the organization

With the primary pain points and systemic flaws identified, the team created a list of key transformation opportunities. Simply fixing one area would not be sufficient. A look at the end-to-end internal and external journey was necessary, and some hard choices had to be made.

The project cornerstone was to integrate the three entities into one centralized department, combining RO, CI, and CA under one legal entity, renamed the Commission for Labor Disputes Settlements. Now all three departments would be under one roof, with space planned for current and future capacity requirements.

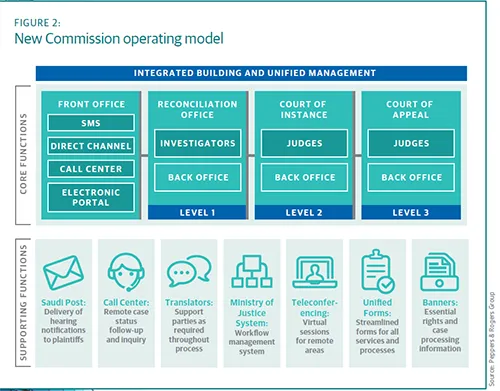

Next was to remap the operating model, so channels and roles were more clearly defined (see Figure 2).

As part of the new structure, the team re-engineered processes to eliminate waste and streamline operations. For example, employee job descriptions were re-evaluated and changed to minimize overlap and optimize resource utilization. And compensation was tied to multidimensional evaluation metrics and merit-based financial incentive programs. The Commission also leveraged outsourced partnerships for courier and call center services, so it could focus more time on labor disputes. Outsourced couriers deliver session notifications by mail and provide proof of delivery quickly. And with new call center resources, defendants are now proactively contacted about upcoming sessions, and people can use the channel for general and case-specific inquiries.

The Commission’s technology infrastructure was bolstered, as well. For example, an electronic case management system was put in place to organize case registration and scheduling, interlink operations among the Commission’s’ three divisions, connect with external partners, and allow remote monitoring of key performance indicators across the entire organization. The Commission also installed high-definition teleconferencing rooms in remote offices around the Kingdom so people could conduct sessions and interact with the central office without having to travel. By removing travel burdens from the equation, the duration between sessions diminished significantly.

Lack of communication was a big challenge, so the group created and hung banners and posters at strategic locations throughout the country highlighting labor law rights, along with answers to frequently asked questions about the labor dispute process. The information is presented in Arabic, English, and Urdu. In addition, centralized translation services are now available in three major Commission offices, removing language barriers and providing all parties with equal chances at every level of the process.

The team started with a pilot project in two cities—one large metropolitan area (Main City), and one in a rural, remote location (Rural City). Main City accounted for 25 percent of the total population, so any benefits there would help many people. And piloting in the Rural City allowed the team to build know-how and understanding for the many other similarly profiled cities located in the far corners of country.

Overcoming obstacles

There were challenges when implementing many of these changes. Public sector bureaucracy, for example, is one of the toughest challenges to overcome when working with a government agency, because it’s an institutional issue. The layers embedded into the system cause extensive delays from operation departments to supply/approve critical items such as buildings, electronics, furniture, and employees. Also common among government projects is the low level of employee proficiency. Poor legal/computer/interpersonal backgrounds of employees contributed to slow learning curves, as did poor data compliance. And for this project, the remoteness of regions caused delays in delivering equipment and difficulties in finding adequate transportation and lodging.

Making an impact

Despite the hurdles, substantial improvements emerged only six months into the project. The Main City now accepts more than twice as many cases, reduced the duration required to process a case by more than half, and increased investigator and judge productivity by twofold since efforts kicked off (see Figure 3). In Rural City, about 80 percent of the case duration was reduced. Further efforts are underway in the remaining 25+ cities of the country.

Employees in all cities report through surveys and interviews a lighter workload, higher engagement, and overall healthier working conditions. And users underline more practicality, professionalism, and higher levels of service across all channels.

Strategic implications for the long term

As a result of the various initiatives engineered to uplift the Commission’s performance, an average worker is now guaranteed:

• Processing of his/her claim

• Better understanding of his/her rights and the process

• A ruling within a month at each division—RO, CI & CA

• A Fast Track—depending on case eligibility

• Third-party delivery of hearing notification to defendants

• Option to conduct teleconferencing sessions

The noted uplift in performance evidently diminishes the burden carried by both national and migrant workers, reinforcing the Commission’s core objective: guaranteeing a fair trial under fair conditions to all members of the labor market.

On a broader scale, the improvements are a building block for a healthy labor market. Fewer complaints from unsatisfied plaintiffs combined with a drop in negative reviews from international organizations lay solid ground for great leaps in the Kingdom’s image, further propelling a sustainable economy competing for today’s global market.

1 The Disputes Resolution Review – Ch.44, Richard Clark

2 http://excelle.monster.com/benefits/articles/2982-the-worlds-20-worst-pl...

3 http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2014/05/28/worst-countries-workers_n_53896...