Why do some people make ‘illogical’ decisions, even when they think they are being rational and consciously weighing up their options? Is their thinking flawed, or is our understanding of their decision-making process imperfect?

Companies, especially data teams, understand that logic is only a part of a larger equation. They strive to find the missing data that can complete the puzzle. So how can companies get better at predicting what might be at first considered illogical? The answer is to dig deeper into what emotions influence decision making and customer sentiment.

In general, companies do a pretty good job of measuring and predicting the ‘who, what, where, when, how, and how much’ of customer interactions and forecasts. But understanding the ‘why’ is complicated, especially when people are concerned. Humans are neither wholly logical or wholly illogical – we’re biological; somewhere in-between. I know that even if we meet all our client’s stated needs, there is a still a good chance we won’t make the sale and a lot of it will be down to not considering their unstated needs – the way they feel now or want to feel.

Understanding the role of emotions in decision-making is critical if we are to design and deliver customer experiences and relationships that matter to the customer and set us apart from competitors. As Maya Angelou once put it: “I've learned that people will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel.” Yet most organizations are poor at understanding their customers’ emotions and even fewer can use this insight to direct their sales, marketing or service operations – especially in anything approaching real time.

Having worked with data and analytics for nearly 20 years, I’ve always known that even the best analytical tools often fall short of explaining the complexity of human behavior. Over the last year, I’ve been searching for an answer– it’s something I call the Customer Experience Vector (CXV).

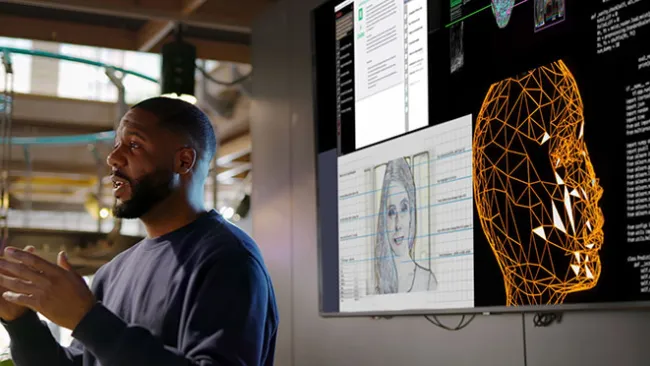

CXV is when data and behavioral science meet; using analytic tools to tackle both the factual, logical portion of experience with the emotional, unconscious portion. One studies the level of emotion in language and context; which is then combined with impact analysis of quantifiable observations (for example, from customer journey analysis).

For example, I put my car in for a standard 10,000-mile service with my local garage. When I collect that car later that day, I am told it couldn’t be completed because of a lack of parts. As a result, my overall level of goodwill towards the garage might drop a little, but I am not too concerned. We agree a date for me to bring the car back—the timing isn’t great (also mildly irritating), but I can plan to work from home that day. On the second day, the garage phones me to say that everything hasn’t arrived and I will have to book another date. Clearly, each event isn’t too dramatic but they begin to add up—perhaps I start to think about getting my car serviced elsewhere, or I may be more responsive to a competing garage’s marketing.

As human beings, we can intuitively assess the impact of this case, but what if we are large organization, with millions of customers, lots of channels, and a constant stream of data points? It’s here where CXV can support large-scale, automated decision-making based on individual customer experiences.

It’s important to note, once trained, the model is not dependent upon surveys (although surveys do provide invaluable training data) or narrative from every customer. Simply, it scores everything in terms of the basic emotions felt by the customer; for example, did the event make that customer feel ‘happy’ and by what degree. Whilst not perfect (humans are far too complex and messy for that), CXV provides a fresh perspective of the complexity of human interaction.

Performing such evaluations and calculations as discrete moments in time are themselves only telling part of the story on their own. The CXV models use these assessments to subtly modify a spectrum of individual emotions scores that are unique to every customer. In this way, each customer’s CXV represents a summary of their journey to date, updated in near real time, with an indication of direction and magnitude of travel, rather than an over-fitted trend line or a prediction. For example, to re-use ‘happiness’ again, knowing what Customer A’s current level of happiness is in respect to us, we keep an eye on whether this feeling is changing and how quickly it is. In the end creating a larger picture of a company’s customer experience based off small instances.

CXV can be used as a dependent variable (for example as an enhanced sentiment score / dashboard) or an independent variable (part of a more complex explanatory model). Either way, it is designed to be a practical method of applying emotions on multiple platforms. We can now evaluate not only whether customers meet the criteria for the product or campaign, but also whether they are likely to be emotionally interested or if there is a better course of action to take.

In a world where more sectors are becoming commodities, it’s harder to tell individual suppliers apart. To stand out from the crowd, they need to realize that it won’t just be the product that defines CX success. Future success lies in the ability to delve deeper into data insight to better understand and take action for each individual customer. CXV adds one more tool to a company’s arsenal.

How to Quantify Happiness, and Other Emotions