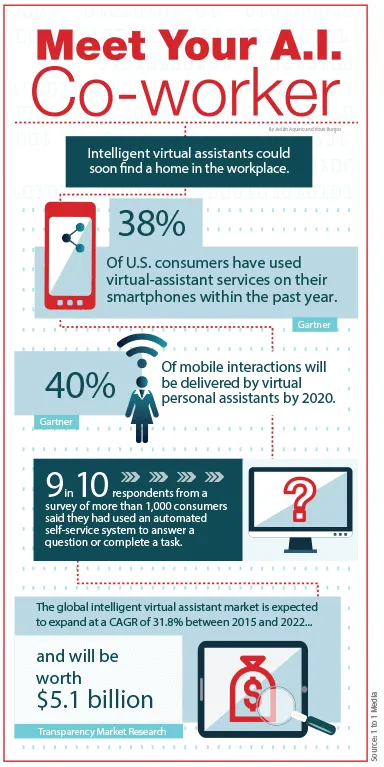

Do virtual assistants need a personality? If so, what defines the personality of a virtual assistant? Questions like these are becoming increasingly relevant as virtual assistants that are powered by artificial intelligence begin to transform the customer experience.

It may not be as obvious as a robot greeting customers at the door, but bots and virtual assistants are serving customers. Through a partnership with Amazon, Domino’s lets people order pizza through Amazon Echo’s virtual assistant, Alexa. Pizza Hut is using Facebook Messenger’s chatbot to power a social ordering platform where customers place orders for pizza. The bot will also answer questions about the food, Pizza Hut deals, and even offer menu items that are localized to specific stores.

Additionally, Macy’s is testing “Macy’s On Call,” a mobile Web tool that allows customers to interact with an A.I.-powered shopping companion on their phone. The tool, which is being piloted at 10 Macy’s stores, taps IBM Watson, via Satisfi, an engagement platform, to answer questions like, “Where are the ladies’ shoes?” These bots or virtual assistants offer new ways to ask questions, make purchases, and more. But as virtual assistants take on tasks that were primarily handled by humans, do they need a personality too?

Personality, defined

Merriam-Webster defines personality as a “set of distinctive traits and characteristics.” Humans have long been judged by the qualities that make up their personality. We are hardwired to look for signs that reveal someone’s personality from the firmness of his or her handshake to eye contact.

Traditional robots, on the other hand, have the opposite of a personality—they are built to behave in predictable, identical ways. But as virtual assistants evolve from being purely command-driven to something close to a companion, it’s logical that they would be more relatable.

Before Siri dispensed weather forecasts and jokes, there was SmarterChild. Launched by ActiveBuddy in 2001, SmarterChild was a chatbot that America Online Instant Messenger users could add to their buddy list. SmarterChild provided facts and figures, airfare rates, movie times, and other information in a conversant style with AIM users. SmarterChild was so popular that ActiveBuddy claims the bot received more than 2 million “I love you” messages within the first four months of its operation. But it appears SmarterChild was before its time. Microsoft acquired ActiveBuddy (which had changed its name to Colloquis) in 2007 and eventually shuttered SmarterChild.

Even though SmarterChild was just pulling information from domains and knowledge bases, it was an early example of how readily people will converse with a bot. In order to be successful, a robot must be engaging. And the more personable it is, the “stickier” it is. The challenge of course, is to design a robot or virtual assistant that is relatable without being creepy.

What’s in a name?

Names play an important part in establishing perceptions of an individual’s personality. Anyone who has skimmed through a book of baby names knows that names are associated with certain characteristics. And for better or worse, many A.I.-powered virtual assistants have been given female names along with female voices such as Alexa, Siri, Cortana, and Nina. However, developers are starting to move toward other options, like Google, which simply named its A.I. assistant “Google.” And iPhone users now have the option of switching the gender of Siri’s voice to male.

We can expect to see companies roll out more options to personalize their virtual assistants as a differentiating feature. In fact, Google has patented its personality development system. In a patent that was awarded to the company in 2015, Google outlines ways to download and customize the personality of a computer or robot. The patent includes a description of a cloud-based system in which users download personalities for the robot as if they were downloading an app.

The robot could potentially contain multiple personalities or accounts for interacting with each user. As the patent states:

“The robot personality may also be modifiable within a base personality construct (i.e., a default-persona) to provide states or moods representing transitory conditions of happiness, fear, surprise, perplexion (e.g., the Woody Allen robot), thoughtfulness, derision (e.g., the Rodney Dangerfield robot), and so forth. These moods can again be triggered by cues or circumstances detected by the robot, or elicited on command.”

Furthermore, the robot may be “programmed to take on the personality of real-world people (e.g., behave based on the user, a deceased loved one, a celebrity and so on) so as to take on character traits of people to be emulated by a robot.”

It remains to be seen how Google will apply this patent to its products—will we have multiple Rodney Dangerfields walking among us? But it’s clear that the company understands the value of creating robots with customizable personalities.

Key challenges

From HAL and the Terminator to C-3PO and more recently J.A.R.V.I.S., Hollywood has an unending fascination with artificial intelligence and robots. But in reality, we’re a long way off from interacting with the humanoids you might see in a film. There are numerous questions that must first be answered.

For instance, before virtual assistants can communicate with each other, there’s a question of who ultimately owns the data that’s exchanged. If your virtual assistant communicates with a bank’s virtual assistant to perform a transaction, who protects the data as it goes through? And if something goes wrong, who will be held responsible? Questions like these will have to be answered before virtual assistants can become truly useful.

Also, developers must establish a set of parameters around what is considered an appropriate response as they train robots to interact with humans. Tay, the artificial intelligence chatbot that Microsoft introduced on Twitter, demonstrates the importance of creating guidelines. Tay was designed to learn how to engage with people through “casual and playful conversation,” Microsoft said in a statement. Unfortunately, many of the conversations were hardly playful. People tweeted a stream of offensive comments at the bot and in less than 24 hours, Tay was repeating those sentiments back to users.

What to expect next

It’s unquestionable that personalities, or something close to it, are quickly moving from a nice-to-have feature to an essential part of robots. Personable robots that can engage people in useful and delightful ways will become a key competitive factor. And while we’re still a long way off from creating truly conversant robots, it’s safe to assume that companies are racing to get there first.